It would be a supreme irony if a part of environmentally-positive power production halted the possibility of “green” aviation by making it unsafe to be in the skies. Luckily, this might not be the major problem some perceive, and solutions are in place or being developed.

For a brief time last April the United States Air Force held up construction of an eastern Oregon wind farm that will be the largest in America. Concerned with the possible interference that 300 new giant wind turbines might cause for radar station transmissions in an otherwise remote part of the state, the Air Force stepped in. That was a short-lived interruption, with Oregon’s Senators countering with concerns about the 706 jobs, $130 million in taxes to local counties over two decades and $2.7 million in royalty payments to farmers and ranchers that would be lost by shutting down the project, even though the Federal Aviation Administration issued a “notice of presumed hazard” that halted construction of towers above zero feet in height.

According to the Oregonian report, “Air Force Gen. Gene Renuart, head of U.S. Northern Command, testified before Congress in March that the military is increasingly concerned about wind farms disrupting radar. The number of U.S. wind projects is growing fast amid increasing demand for renewable energy and plentiful government subsidies.”

The 338 turbine project would generate 845 megawatts, enough to supplant a coal-fired facility in nearby Boardman, Oregon that has been a source of contention with local environmentalists.

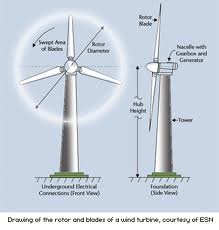

The Air Force told the Oregonian, “The Shepherds Flat turbines – combined with about 1,800 other turbines built or proposed within the Fossil station’s range – would ‘seriously impair the ability of the (Department of Defense) to detect, monitor and safely conduct air operations in this region.’” The Air Force contends that tall turbines can “reflect radar signals, creating a blind spot that can erase airplanes on radar screens. The turbine’s rotating blades can also clutter the screens, creating a radar signature that constantly changes as the blades slow down or speed up in the wind.”

Industry officials say they’re working on radar friendly turbine technologies. Upgrades to radar stations – possibly financed by the wind farms – would also help. Modern systems are much less affected by spinning turbines.

Oregon Senators Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley, and U. S. Representative Greg Walden lobbied the White House and Pentagon while putting three Defense Department nominees on hold to allow Defense Secretary Robert Gates, to agree that “homeland security concerns shouldn’t thwart home grown renewable energy.” Senator Wyden said, “It was clear to me that he understood it was possible to do both.”

In the meantime, radar experts at MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory reviewed the project, and Air Force and industry personnel agreed to work on solutions that would mitigate loss of radar tracking because of turbine activity.

The hubbub was significant enough to evoke a response from Britain, with Flight Global’s John Croft reporting, “The green roadblock is an example of a growing number of aviation-related compatibility issues arising from renewable energy projects, many of which are located at or near aviation infrastructure. Although solutions are usually found, an expected rise in the number of proposed projects is prompting regulators to be proactive in setting out ground rules.”

Croft further explained, “Dangers can also precede the installation of turbines. Low-level operators for firefighting and other missions in the USA are being warned of 122-152m (400-500ft)-high temporary meteorological test towers that are being installed at potential sites for wind farms to determine whether the site could be profitable.

“Aviation officials in Idaho say the slim towers are difficult to spot if not marked, are installed in a matter of days, and can be gone in 12-18 months. Many pilots have ‘close call’ stories to relate.”

Flight Global’s David Learmount had reported in 2006 that, “BAE Systems has developed a bolt-on, two-chip radar signal processor that can negate the radar-confusing returns that wind turbines generate. The advanced digital tracker (ADT) does not interfere with the radar, but post-processes the signals before they are shown on the display, dismissing the clutter the turbines can create so “real” targets can be detected even close to large wind farms.”

Because wind turbines have a total radar cross section of 1,000 square meters (11,000 square feet), and the turning blades “confuse the Doppler-based moving target detectors that primary and secondary radars use,” the potential for problems abounds.

Originally developed to separate missile radar signatures from those caused by wave action in a “harsh naval environment,” the BAE system is a small device that can be “bolted on to any type of radar, and consists of an interface chip to make it compatible with the unit, and another chip hosting the software.” Algorithms can be fine tuned for a particular site because each wind farm has a unique radar signature. BAE has been working on this “fix” since 2002.

Newcastle airport in the United Kingdom has developed its own software solution for the same problem, one which “blanks” wind farm reflections, “which have the same characteristics as moving aircraft returns and can thus be dangerously misleading for controllers.” Surrounded by wind farms, Newcastle needed a way to separate the turbines on the ground from the turbines in the air. Their “blanking” approach provides a “patch” to cover the existing and potential wind farm sites. By not showing radar images for wind turbines, clutter on the controllers’ radar screen is eliminated and potential confusion reduced.

These developments are important to the CAFE Foundation and researchers working on ways to “free up” general aviation from the current controller-based air traffic systems. The fifth annual Electric Aircraft Symposium, coming in late April, will address many of these issues and their potential solutions.