Appearing before attendees at the 2013 Electric Aircraft Symposium, Randall Fishman’s spoke of great accomplishments and grander visions. “ElectraFlyer ULS & Electric Ultralight Airplanes, the path to approval for all electric aircraft?” showed ElectraFlyer’s history and the ambitions Randall would like to play out.

A pioneer in ultralights, Randall has been flying hang gliders since 1972, produced the first continuously powered electric aircraft, flew the first electric airplane at Oshkosh’s AirVenture and claims a primary interest of bringing practical, user-friendly electric flight to as many people as possible.

Between 2005 and 2007, he designed, built and test flew his first electrically-powered trike. Making its first take-off on April 29, 2007, by May 2 it had made a one-hour flight. Ever more venturesome, Randall modified a Moni motorglider with an electric motor and flew that at AirVenture in 2008, for which he won both the Stan Dzik Memorial Award for innovation and the Dr. August Raspet Memorial Award for “outstanding contribution to the advancement of light aircraft design.” His motorglider cruised at 70, topped out at 95 mph and could stay aloft for 1.5 hours – a truly practical light airplane.

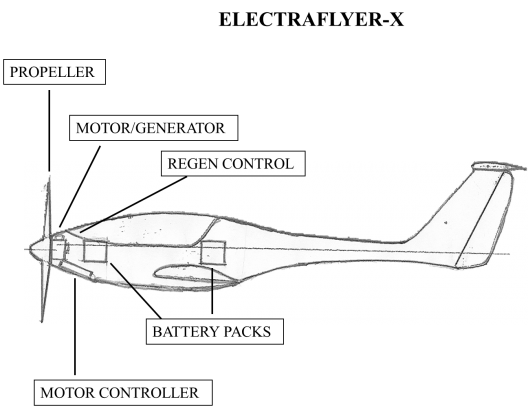

His two-seat X project has been placed on hold until FAA approval, but in the meantime, he sold an experimental kit of parts to Richard Steeves of Madison, Wisconsin. Richard has been working on construction and looks forward to beginning motor runs later this year. Randall used a profile of the X to show the potential for hybrid power, something also discussed by the e-Genius and Pipistrel teams. Comparing the operating costs between typical general aviation craft and a practical hybrid LSA, Randall showed that pilots could count on half the fuel burn at only one-third the cost per flight hour. This would be a huge draw for new pilots and aircraft owners.

His new ElectraFlyer ULS (Ultralight Soaring) fulfills his goal of bringing practical electric flight to as many as possible. Randall started work on this production ultralight in 2008 which has been available for purchase since late 2012. Randall has logged 31 hours in the machine before he appeared at EAS VII.

Randall has worked for the last two years with a Czech Republic manufacturer and Slovakian designer to design and build the twin-boom electric ultralight – for which Randall has worldwide distribution rights. To keep the airplane within Part 103 rules, the structure is a marvel of lightness and clever design tricks.

The trailing link landing gear, for instance, is a bungee-suspended unit that works well on paved or grass surfaces. Its light weight belies its strength.

Each 40-pound wing panel allows easy one-person assembly and disassembly. Because its tail structure is fixed within the two-meter center section, a pilot does not have to rig any controls other than one pin on each wing, simplifying what otherwise can be an arduous task.

The motor on the ULS produces 20 horsepower at 2,500 rpm, generating thrust through a 53-inch, carbon fiber over foam propeller – which can be folded to reduce drag in soaring flight. Left to windmill, the propeller can feed current back to the batteries through regeneration, possibly adding to powered flight duration. Since level flight requires only 3.8 kilowatts of energy, the batteries drain slowly.

This compact system is coupled to an efficient controller, and the ability to pick battery packs that meet specific missions gives the ULS flexibility of operation.

Randall notes that each well-ventilated battery box, a slim stainless steel module that can fit into a slot in each wing root, can hold one or two battery packs. With a single pack in each module, the ULS’ light weight enables soarability even on light days. Putting two battery packs in each module enables up to two hours of powered flight.

With the motor off, the 36-foot wing gives a glide ratio of 20:1 and a sink rate of 234 feet per minute. Not quite an Antares, but at $59,000 ready to fly, not quite the $280,000 of the German superplane. Randall explains that a small group or club could have an efficient self-launcher that can use regular airports and runways, and reduce or eliminate wait times for tow planes, launch queues and other impediments to soaring joy.

Instead, a pilot can regularly enjoy solar-powered flight, expressed as thermals and ridge lift when heavier sailplanes or even hang gliders are grounded for lack of “good” soaring conditions. Randall reports being able to motor to just the right altitude to catch lift, conditions which sailplane pilots on tow sometimes miss or cannot take advantage of because of low altitudes.

The manufacturer makes a version of the airplane that can be powered by a single-cylinder, four-stroke Bailey V5 or a short-wing version that can be accommodate a Verner JVC-360 two-cylinder engine. Only the electric version, though, has both flaperons and spoilers. Randall says the spoilers are highly effective in dropping altitude quickly despite their small size.

Randall Fishman uses flaperons, spoilers to land on the selected spot during windy day. Camera on right rudder captured flight on video

Looking beyond the USL, Randall has a trio of motors; 30, 60 and 90-horsepower waiting in the wings with news to come soon.

Explaining that a production airplane such as the ULS is essential to getting electric aircraft in the sky in large numbers, he noted that even dedicated home-builders would take years to get a single airplane to demonstrable success, making for a small representation within general aviation. Randall’s inventive mind is obviously in top gear these days, seeking out new ways to bring electric flight to a broader audience and expand the number of proven electric craft. We can only wish him good fortune with his ventures.

Comments 2

I really like this airplane. Just the ticket for local fun soaring without waiting for a towplane. I’d love to see a video showing the soaring performance. I am a bit curious about the Part 103 claims, however. Under Part 103, the maximum allowable stalling speed is 24 knots. Judging by the video, the takeoff and landing speeds were way higher than that.

Hi Mike. Yes I carry extra speed during landings but still touch down at about 30mph. Legit stall speed under the part 103 limit is assured. Also the wide angle lense of the go pro camera in the plastic case is making the speeds seem higher.