In the Innovation Pavilion at Oshkosh’s AirVenture 2013, Joseph Hutterer quietly drew people in with a model and an interesting approach to a single-fuel type of hybrid. Take the twin engines off the wings and place one of them in the modified tail. Now put a small turbojet in a retracting pod in the nose. Taxi out to the end of the runway and use both engines to take off and climb, then shut the nose jet down, retract that, and cruise on the single rear engine.

Hutterer, with an Aeronautical Engineering degree from the University of Minnesota, FAA commercial pilot’s license with single-engine, multi-engine, instrument and glider ratings, and 42 years of engineering and marketing experience in the general aviation industry, has the credentials and the patents to make his approach credible.

Consider that aircraft such as the Solar Impulse cruise on only about 10-percent of what they need for takeoff and climb. A typical business twin doesn’t have the long wings and ultralight weight of such a creation, but it can climb on one engine if necessary. The extra thrust from the second engine adds to the performance, but adds drag and control issues. Hutterer claims his retractable second engine does not induce asymmetry into the mix when deployed or retracted, and that the absence of a nacelle or propeller (even feathered) reduces drag for the primary engine to overcome.

Since both engines are turbines, they feed from a common fuel system, simplifying operations. With only the rear turboprop in operation, fuel burn and emissions are 40-percent lower than with conventional twins. If the rear engine suffers a failure, the front engine can fly the airplane to its destination.

Hutterer holds United States patent 7,549,60, good for 20 years and for any size aircraft. He sees the implementation of that patent as important to addressing the continuing increase in fuel costs (and the implied loss of 100-octane low-lead avgas), increasing demands for reduced CO2 emissons, the desire to reduce oil imports to the U. S., especially from unfriendly countries (a process already in progress), and the public perception that business jets are an unjustified luxury.

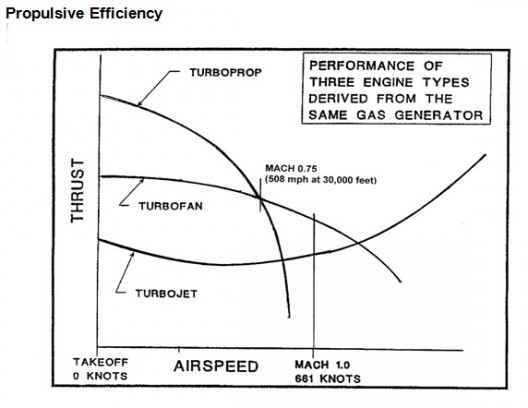

Hutterer notes that the chart shows the turboprop engine being outstanding in giving high cruise speeds while dropping fuel demands. He claims that, up to Mach 0.75, where the turboprop loses efficiency, its efficient acceleration of large masses of air makes it competitive with slower pure jet aircraft. Whether this will change perceptions of businessmen luxuriating in high-speed, high-altitude comfort remains to be seen.

Efficiency is important, even for those with money to burn, so improvements which promise the kinds of fuel savings coupled with safety and performance may find favor in the business aircraft world.

Comments 1

This is reminiscent of an idea put forward by Flight Design (I believe), who proposed a battery-powered electric boost on a gasoline engine. As motorglider pilots know, if the airframe is low-drag, you don’t need a lot of engine to power it, but you still need power for takeoff performance. Most airplanes size the engine for takeoff, but Flight Design proposed sizing it for cruise (too small for takeoff) and adding short-term electric boost for takeoff and initial climb.