An Electric Great Air Race

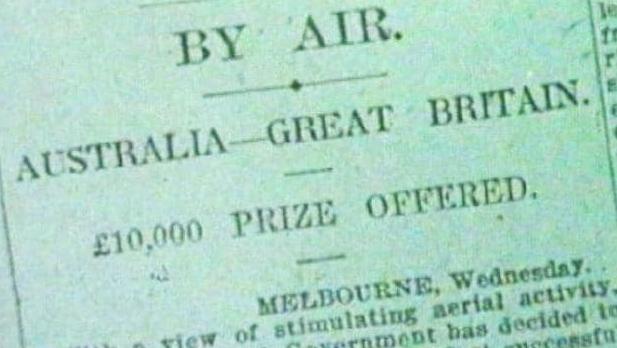

100 years ago, a great air race – “The Great Air Race” – in fact, was held with competitors flying from Great Britain to the Northern Territories of Australia. Crews had 30 days to make the trip, and considering the reliability of engines at that time and the primitive nature of aerial navigation, very little time to relax.

Of the six teams that entered, only two made it, three crashing (two fatally) and a fourth team being imprisoned in Yugoslavia as suspected Bolsheviks. Only two teams finished, and only one received the 10,000 Pound Sterling prize (about 544,577 pounds today – over $775,000), enough to cause the six crews to accept the high risk involved.

Captain Ross Smith with 10,000-pound prize money – equal to over a half-million today

The winning flight, in a Vickers Vimy WWI bomber, inspired the founders of Qantas to begin regular airline service in the country, with that company, nearly a century later, able to offer transit from Los Angeles to Sydney for under $1,500 (under $100 in 1919 currency). They have just added non-stop flights from Europe to Australia with Qantas’ great reliability and safety – a far cry from the derring-do of 1919.

“On the morning of November 12 1919, pilots Ross and Keith Smith, along with mechanics Sergeants Wally Shiers and Jim Bennett, took off in their Vickers Vimy G-EAOU from Hounslow aerodrome in West London.

“Over the next 29 days they passed through countries including France, Italy, Greece, Egypt, Iran, Pakistan, India, Myanmar, Singapore and Indonesia before touching down at Fannie Bay, Northern Territory.

“The realization that it was possible to fly from Australia to Great Britain was part of the inspiration that spurred the founding of Qantas, by Paul McGinness and Hudson Fysh, in 1920.”

Richard Glassock, a fellow at Nottingham University, emailed to report on plans to recreate the 1919 race and even a better-equipped 1934 air race from England to Australia, the MacRobertson Trophy Air Race.

Richard thinks the use of fuel-cell-energized, electric, all composite craft noted in contest rules will be the kind of technological leap that took place in the 15 years between the Great Air Race and the MacRobertson.

His interest in the projected event is echoed by University of NSW Emeritus Professor of physics John Storey, who said the race would help spur innovation in battery technology.

“The heart of the problem is to store enough energy in the batteries without making the aircraft weigh like an elephant,” Professor Storey said.

“The event is technically feasible, but being able to complete the route within 30 days is by no means a foregone conclusion.

“That makes 2019 the right time to stage it: in 2009 it would have been impossible, in 2029 it will be routine. It’s a very happy coincidence.”

An overview of the new and electric Great Air Race can be found here

According to Flight Safety Australia, “The 2019 race is sponsored by the Northern Territory government, which has adopted a suggestion made by entrepreneur Dick Smith that the centenary of the original race be marked by a similar race for electric aircraft.

The 2019 race will be for three categories of aircraft:

- Battery electric, which must use batteries, wind turbines or solar power to turn an electric motor.

- Hydrogen fuel-cell electric, which must use the above methods and hydrogen.

- Hybrid combustion-engine electric, which must be series hybrid, without any direct drive between the fossil fuel engine and the propeller or propulsion turbine.

Aircraft can be fixed wing, rotorcraft or lighter than air.

Middle East Short Course Racing

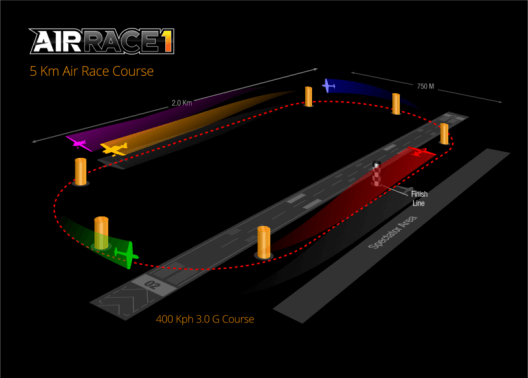

Some will wonder about the range required for even the shortest legs of the Great Air Race. Organizers in Dubai are betting their Air Race E contestants will be able to stay in the air long enough for their eight laps around a five-kilometer (3.1 mile) course marked out by pylons, emulating Formula 1 air races seen at Reno, Nevada.

Air Race E course emulates that of Formula 1 racing

Even with throttles to the firewall, competitors should manage the 24.8 mile course, the G-forces of the turns putting a greater strain on pilots than on the motors or batteries. Conversions of exiting Formula 1 racers or new designs meant to optimize things for electric power should provide plenty of thrills for spectators as the aircraft buzz by, eight at a time.

Less eclectic than the Great Air Race, Air Race E contenders will be limited to electric, battery-powered, propeller-driven craft of a certain weight and size.

Across the Pacific, Electrically

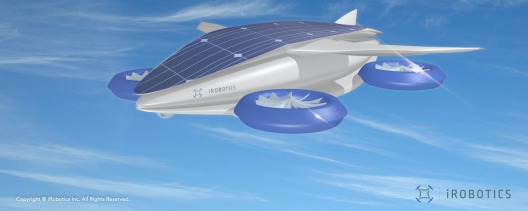

Another event will capitalize on unpiloted craft to make the 4,500 mile jump from Japan to California non-stop. One competitor has accepted the challenge presented by iRobotics of Tokyo. Their audacious idea, to fly from Tokyo to San Francisco, seems like something that would challenge most large commercial aircraft using the best generally-accepted technology of our day. To add that the airplane will be unpiloted and powered by electricity adds a level of difficulty that makes this seem almost ludicrous.

Even iRobotics, in a Red Bull-sponsored web page, sees the almost implausible nature of their dare to others.

iRobotics trans-Pacific drone challenger

“A Japanese drone start-up is throwing out a challenge to all comers for a drone race from Tokyo to San Francisco. It sounds far-fetched, but a lot indicates that the race could happen much sooner than you think. Even if drones taking part will need AI, flight-control software, sensors and batteries that hardly exist today.”

Sabrewings Draco-2, a competitor for the trans-Pacific Drone Race

So far, they have one challenger, Sabrewings Aircraft, headed by Ed De Reyes. A test pilot, a flight test engineer, and an FAA liaison for small and large companies alike, on various programs and projects. Ed is the Chief Executive Officer and co-founder of Sabrewing.

Both the iRobotics machine and the Sabrewing Draco-2 UAS are reputed to be capable of the 4,500 mile trip, and will feature dazzling arrays of technology and clever design. For the Draco-2, Sabrewing lists the following:

“The DRACO-2 is designed to fly non-stop and un-refueled for 4,500 nautical miles (8,800 kilometers). It launches from a standard runway, and provides near-real-time video from on-board the air vehicle for the first 150 miles of flight. At cruise altitude, it then switches to high-resolution, low-light, on-board cameras that are updated every 5 seconds and provide a view of the aircraft path and the air vehicle’s location over land or water. Day or night, good weather or bad, the Rapier has the capability of flying for days without stopping or refueling.

“For added safety, the DRACO-2 has a unique, proprietary sense-and-avoid sensor suite that detects objects that may conflict with the air vehicle’s flight path – and can instantly turn right or left, climb or descend – to autonomously avoid anything in its way…even as small as a bird. The DRACO-2 can even fly safely on two rotors – and every essential system on board is redundant to assure mission completion.

“The DRACO-2 is controlled via satellite, and is in constant communication with both the Launch and Recover Element (“LRE” – located at the launch point in Japan) and Mission Control Element (“MCE” – located at the destination landing point of Moffett Field, Mountain View, California, USA). The air vehicle is monitored by two pilots on the ground, in constant contact with Air Traffic Control. The trip is expected to last about 45 hours – and provide spectacular views of the air vehicle and its flight path – both day and night – while in flight.

“The entire flight – from takeoff, climb, cruise and landing – will be available on the Pacific Drone Challenge website.

iRobotics, in tendering its challenge, is fearless in taking on all challengers. They explain, “It might initially sounds strange, but iRobotics are hoping that giants like Boeing, Airbus, Google and many others will rise to the challenge. The Japanese start-up is not afraid of taking on companies that are easily 1,000 times bigger than them.

“It’s a gamble, of course. However, we feel that the race is a unique proposition that can help develop drones. We are pushing technology, making it capable of solving some of the challenges the human race faces. At the same time, it’s no secret that we’re hoping to make a profit, which I don’t think is wrong. It’s a situation where we’re having fun working on something we’re passionate about, which we believe will have a positive impact on the world, while challenging the idea of what can and can’t be done. It’s pretty much a perfect recipe,” Yoshiyasu Ando (CEO of iRobotics) says.

With three major electric air races with different goals, we might see a new golden age of (electric) air racing in the next few years. Racing does improve the breed, as great car makers have long known.

Comments 1

Qantas-Acronym for ‘Queensland & Northern Territory Air Service’

NO U in Quantas!!