Contrails are the trails of condensed water vapor that follow an airplane at a high enough and cold enough altitude. They became a visible presence in World War II and were part of newsreels of allied bombers hitting Germany and dog fights over the English countryside. There was more than just an aesthetic side to the new, high clouds in the sky, though.

WWII saw the introduction of massive waves of high-altitude fighters and bombers, as depicted in this 1965 British postage stamp

Post-9/11

During the attacks on September 11, 2001, FAA controllers, “Did the only thing they could think of to try to control the situation: ordering every aircraft in U.S. airspace, about 4,000 of them, to land somewhere, anywhere, immediately.”

“Canadian officials followed. Airports in Atlantic Canada quickly filled with thousands of bewildered people who had been flying west across the Atlantic from Europe, but found themselves stranded in Goose Bay, Labrador or Stephenville, [Newfoundland].”

Following this mass grounding, an observable cooling took place. Andrew Carleton, a geographer at Pennsylvania State University recalled his observations at the time. “I remember walking to and from my office (in the days after the attacks) and thinking how incredibly clear the skies were.”

About a year after the attacks, Carleton, David Travis, and another colleague argued in a paper that thin clouds created by contrails reduce the range of temperatures. Adding to cloud cover during the day, they reflect solar energy that would otherwise reach the earth’s surface. At night, they trap warmth that would otherwise escape. Not surprisingly, temperatures change most in areas where the most flights take place.

In this video, Carleton explains the effects contrails have on heating and cooling the earth.

In a reversal of 9/11 effects, an air raid involving over 1,400 aircraft over England in May, 1944 measurably lowered daytime temperatures. This was in a time when only a few airliners departed London each day and private aviation was the province of the well-to-do.

In 2004, NASA scientist Patrick Minnis wrote that “increased cirrus coverage, attributable to air traffic, could account for nearly all of the warming observed over the United States for nearly 20 years starting in 1975.” He attributed a one-percent per decade increase in cloud cover came from increased air travel, greater in more populated areas and in winter, “when contrails are bigger.”

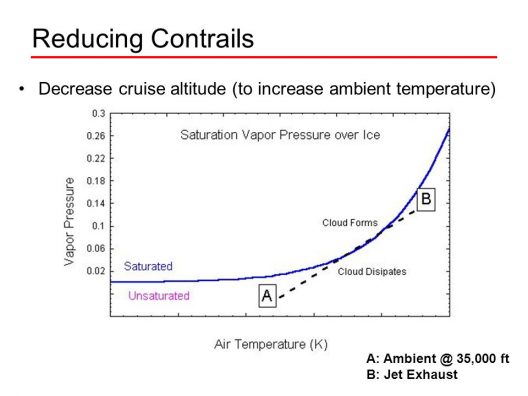

A 2005 paper by physicist Robert Noland of Imperial College London suggested, “restricting airliners to 31,000 feet, and 24,000 feet in winter, could reduce the formation of contrails. Though lower-flying planes would be less fuel-efficient.” NASA pursued that line of thought at around the same time.

Flying a lower altitudes prevents contrail formation, but would probably cut into airlines’ profit margins without new designs for aircraft

Minnis found, “The warming effect happened because the high-altitude clouds that contrails created tended to trap warm air. On balance, though contrails can both warm and cool, there is more of a warming effect.”

A 2015 Penn State study expanded the 2001 finding by comparing regions of the United States where contrails tended to form more strongly with areas where they didn’t. The more contrail-heavy the area, the less the variation between daytime highs and nighttime lows tended to be.

Higher Fuel Efficiency, More Flights

Maddie Stone, a science writer for Gizmodo, explains in a recent article that, “The climate impact of flying isn’t just about carbon emissions. The contrails that airplanes create also influence the temperature of our atmosphere—and a new study finds that impact is set to grow in a big way. She explains, “Globally, the atmospheric warming associated with these clouds is estimated to be larger than that caused by aviation’s carbon emissions. That surprising fact has some scientists curious about whether the effect will grow as the skies continue to get more trafficked into the future.

Stone references researchers at the German Aerospace Center (DLR) and their findings published in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, “show that by 2050, contrail-induced warming could be three times higher than it was in 2006. In fact, this type of warming will likely outpace warming from rising carbon dioxide emissions, thanks to concurrent improvements in fuel efficiency.”

Stone adds, “The authors’ models indicate cirrus clouds will contribute some 160 milliwatts of additional ‘radiative forcing’—extra energy flowing back toward the Earth’s surface— by mid-century. Ethan Coffel, an atmospheric scientist at Dartmouth College who wasn’t involved with the paper, noted that for comparison, under the climate change scenario the authors use, heating from greenhouse gas emissions will be around 6,000 milliwatts per square meter by the end of the century.”

As contrails persist at altitude, they shield the earth from the sun’s radiation, but also trap heated air beneath

“’So while the contrail forcing is certainly significant, it’s a relatively small contributor to overall warming,’ Coffel told Earther via email.”

It will be a net cooling effect for jet engines to become more efficient and a net warming effect as flights become more frequent. Some are urging flying less or not at all. That will demand more rail, bus and private car traffic, though, with possibly great effects on warming.

Geoengineering?

Some want us to turn to geoengineering to solve this crisis. Again, the unintended consequences might be worse than the problem. Should we create high, reflective clouds to radiate solar warmth back into space? Should we work to get rid of all clouds? Either route seems to have a disaster-movie scenario attached. Your editor just finished reading Richard Rhodes’ Energy: a Human History. The book relates the many changes in energy production through time, with each promising much, but having sometimes tragic effects on those who accepted the new “technology” with open arms. With so much riding on our newly-forced choices, we must be as informed as we can be while practicing the highest levels of due diligence.

More to Read and Ponder

A final note: This link provides a good overview of post-9/11 research on aircraft contrails and their effect on climate. Obviously, an electric alternative would be a great one – but we’re still short on the necessary battery technology.

The site warns, “If any of the links above do not work, copy the URL and paste it into the form below to check the Wayback Machine for an archived version of that webpage.”