Dragonfly is a great name for the tandem-wing, two-seat aircraft, with the forward wing mounted low and the rear wing higher and behind the cockpit. Students at InHolland University of Applied Sciences now have two of these anisoptera-like craft they are converting to electric power. Considering there are only two such airplanes registered in The Netherlands, 100 percent of all Dragonflies in the country will soon be electric. Over 500 have been completed worldwide in the last four decades.

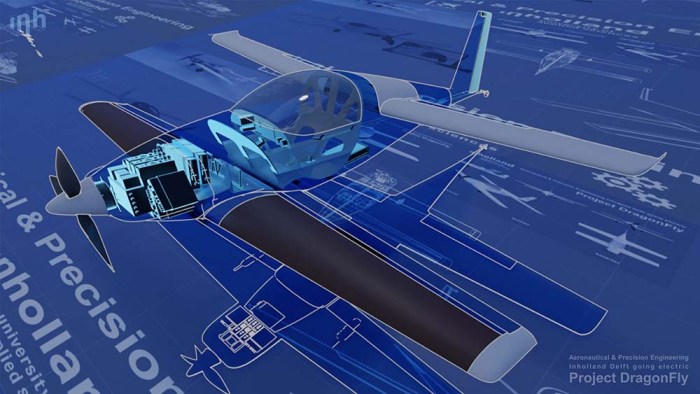

According to the school, “The airframe design is visually similar to the RAF’s Quickie 2, which was developed independently, but the Dragonfly has larger airfoils and was designed for a smaller engine, resulting in a slower but more docile handling aircraft. Originally 60 hp (45 kW) Volkswagen air-cooled and 85 hp (63 kW) Jabiru 2200 four-stroke powerplants were used with the Dragonfly. With a redesign to a battery-electric variant [Project DragonFly] Inholland and partners want to demonstrate the viability of electrifying existing small aircraft for… general aviation.” The team has developed two powertrain strategies apparently, visible as a single motor in one version, and a speed-reduced pair of motors in the other. Motors are supplied by Saluqui.

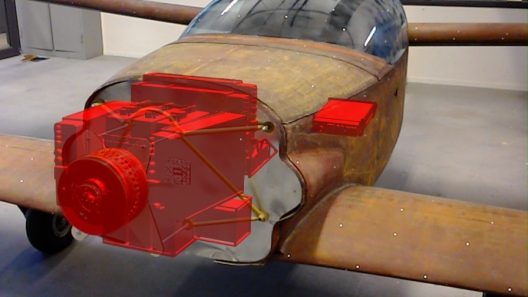

Combining virtual and real elements, the Delft-based Dragonfly shows single motor, original raw finish. Note compact arrangement of motor, batteries and associated systems

Oversimplifying a bit, project manager Mark Ommert summarizes the planned strategy. “The advantage of electric motors is that they are much lighter. In this case, you replace a 100-kilogram motor with one of 15 kilograms. Then you have the weight of an entire passenger left to spend on your energy source.” Seemingly simple, this requires some rethinking of weights and balances for the craft, and the need for compact power sources.

Envisioning the New Airplane

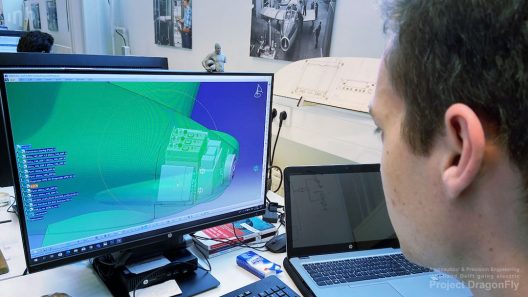

To help visualize how those power sources could fit in their re-imagined dragonfly’s, the team used an impressive array of tools to help “see” accurately the dimensions of the aircraft, and then how to distribute the elements of the power train.

The challenge of dealing with complex 40 year old hardcopy drawings was solved by 3D metrology experts from TetraVision, who used advanced 3D scanning technology. This resulted in a six meter by six meter by two meter 3D model of the Viking Dragonfly airplane with 0.1 millimeter accuracy. This “digital twin” allows for comparison with the actual machine.

Aeronautical Engineering student Kiril Medarov developed a mixed reality application to perform quality checks during manufacturing processes. Able to detect differences between a virtual Dragonfly and the real article allows potential detection of manufacturing alterations or defects.

To enable realistic flight simulation to train potential pilots, Researcher Marco Withag developed a program that will allow them to, “Get used to the flight behavior and onboard systems, before going to take-off in the real Dragonfly. The flight simulation model can be flown in a virtual reality environment, combined with a motion platform that offers three degrees of freedom. This unique combination offers the pilot the opportunity to see and feel how the aircraft behaves under various pay-load configurations and with electrical powertrains.”

Flight behavior of the Dragonfly is modeled using PlaneMaker, a development tool provided by Laminar Research, which backs the X-Plane flight simulator series. X-Plane uses the blade element theory to calculate the forces on the aircraft during flight, according to the Delft team.

Blending It All Together

Modeled and animated in Blender, the free and open-source 3D creation tool can perform, “Modeling, rigging, animation, simulation, rendering, compositing and motion tracking. The model is still under construction but will be available for the public when it is finished, according to the team.

With what appear to be hundreds of students having seen the project and its two exemplars, the program has expanded to include the original donor plane in Delft and the second in Ypenburg, painted in what looks like a homage to Piet Mondrian, the Dutch painter. Two Dutch electric Dragonfly’s may appear at next year’s Paris Air Show. Arnold Koetje Manager of the Applied Sciences Labs, Inholland in Delft shares that ambition. “That will be the concept, although we want to be a long way by then. We also want the aircraft to actually fly by 2023. Koetje hopes that this can also be an example for the tens of thousands of “sport aircraft” worldwide.

Project goals include making a cleaner, quieter, smarter Dragonfly. The lessons learned from these two builds and the tools created to make them possible can be applied to other such conversions of other light aircraft. That’s a gift to all.

Comments 1

Congratulatons, and best of luck with your project! I am the builder of Dragonfly N812RG in Ohio, United States. It is a beautiful and fun plane to fly. It is a perfect airframe for electric motors.

I sold N812RG a few years ago to build another airplane, a Zenith 601XL-B, N601RG.