Ilan Kroo, in a 2014 Electric Aircraft Symposium presentation, showed that a “narrow-body” airliner (for example, the Boeing 737-800) is able to fly one passenger coast-to-coast on 29 gallons of fuel, at about 81 passenger miles per gallon. Driving responsibly, a carpool of four or five in a Prius could show greater operational economy, but take about 40 or more hours to make the trip (and lots of breaks) compared to the five hours in one jump it takes the Boeing. Worse, the same Prius is often stuck in gridlock traffic for short drives with only the driver on board. Even a hybrid’s mileage suffers under such circumstances.

Several popular publications have taken up that “meme” in the last week. Nick Stockton, writing in Mother Jones’ environment section, informs his readers that airlines are already competitive with cars on a passenger mile basis, and that because “Fuel economy is hardwired into the airline industry’s DNA,” there could be benefits for the airlines in promoting green operations, and, “Saving fuel, by reducing carbon emissions, can help save the planet. And those cuts could come at little to no cost to the companies themselves.”

Andreas Schaefer and three affiliated researchers in the United Kingdom put numbers on those premises with their journal article in Nature Climate Change – documenting steps airlines could take to cut emissions in half by 2050. Schaefer is an energy and transportation researcher at the University College of London Energy Institute.

This 35-year paring would require new aircraft designs, something on which Boeing, Airbus and other makers are already busying themselves. Couple that with new fuel formulations and flight patterns, and the change becomes plausible, even profitable, coming about “for free, or pretty close to it,” according to Stockton.

Schaefer explains that commercial air travel accounts for about two-to-three percent of the worlds CO2 emissions. “”If you compare that to the emissions of entire countries, that’s about the same as Germany,” she shares.

The research team chose “narrow-body” airliners like the Boeing 737 series and Airbus A320s as a basis for their study. The have the greatest number of options for emissions reduction because, as with any vehicle used for multiple short-distance trips, efficiency is already low. Airplanes have some potential ways to lower CO2 output by using things like electric wheels with which to taxi, different flight patterns to increase efficiency, and (unfortunately for passengers) making sure every flight carries the maximum number of people.

Most important, reducing fuel use is primary. Richard Aboulafia, an airline industry analyst, claims the airlines to be “the best self-disciplining industry on the planet,” because, “emissions are closely linked to fuel, and fuel is life,” and every iota of carbon emitted shows up automatically on an airline’s bottom line.

With a single narrow body slurping down up to three million gallons of fuel each year, at about $3.00 per gallon, each aircraft costs $9 million just in fuel costs. Reduce that one percent to save $90,000 per year per airplane. Ryanair, an Irish airline, has over 300 737s in its fleet and JetBlue, an American airline, includes 231 Airbuses and Embraers. That one percent savings would make a huge difference in total operating costs.

Because more people are flying every year, airline growth rates are looking like the climate change hockey stick. “In the developing world, the growth rates are significantly higher, up to 7 or 8 percent,” Shaefer says. This is great news for aircraft companies, since the average age of the existing fleet keeps climbing. More established airlines, like American, tend to have older aircraft, while newer operations such as Spirit have newer aircraft.

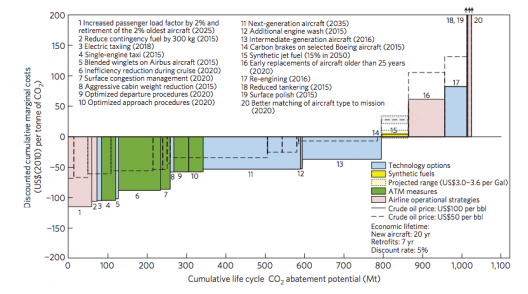

The Nature journal article includes this chart, showing the 21 emissions cuts identified by the authors and ranked in terms of efficiency and cost. The X axis shows the volume of CO2 each mitigation strategy would remove from the commercial airline industry. The Y axis shows the savings or costs for that strategy.

Much of this will depend on fuel costs. If oil stays around $50 to $100 per barrel, “These emissions cuts pay for themselves,” according to Schaefer. If oil prices drop, it will be economically reasonable for airlines to hang on to their old, more polluting stock – much like driving your vintage Caddy when gas falls to $1.00 a gallon.

Some potential greenhouse gas reductions may take more time, such as the development of viable quantities of biofuels. As long as oil is relatively cheap, the incentives to develop these alternatives dim.

Tim McDonnell, writing in Mother Jones, notes that a good deal of progress has been made already, citing studies recent studies. “Michael Sivak, a transportation researcher at the University of Michigan, has found that from 1970 to 2010, the amount of energy consumed per mile, per passenger, on an average domestic flight dropped 74 percent. From 1968 to 2014, the fuel efficiency of new airplanes improved 45 percent, according to the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT).”

Sivak explains that more efficient jet engines and more refined aerodynamic designs are helping push things into the future “with design changes like drag-reducing wingtip fins and a more slippery paint inspired by sharkskin.” Composite construction has lightened commercial aircraft, allowing them to carry more passengers and cargo.

PW1100G-JM First Flight on Boeing 747. Newly re-engined aircraft could have significant operating cost, emission reductions

McDonnell also cites Dan Rutherford, an aviation analyst as ICCT, who explains the average car trip is nine miles, while the average airplane trip is 900. Rutherford explains, “You don’t fly a plane to the corner store.” Cars get better fuel efficiency on highways: airplanes don’t get good mileage at all taxiing from the terminal to the takeoff point.

Despite the fact that improved aircraft, engines, and operating techniques are making aircraft more than competitive with cars over long distances, the effects of emissions at altitude are up to four times greater than for those at ground level.

A proposal from the White House to designate aircraft emissions as a danger to human health might be a blessing. This might force fuel efficiency standards for aircraft, and like Volkswagen’s diesel debacle, encourage thinking along electric aircraft lines to gain environmental advantages.

Toss in military and political struggles in the Middle East, Russia, and Africa affecting how oil will reach us and how much it will cost, and the concerns become pretty overwhelming and the future more ambiguous than we might like to think.