A frustration borne by homebuilt aircraft designers for years has been that of finding an appropriate, reasonably-priced powerplant for aircraft in the single and small two-seat range. Early experimenters often converted motorcycle engines to their ultralight needs. Continentals, Lycomings, and Franklins filled those needs in the 1930s and ‘40s, and other than Rotax and a few smaller manufacturer’s offerings, there really haven’t been any replacements since then. Electric powerplants, however, can be found in the motorcycles being produced by many American and foreign companies now, with more to come from Europe and Japan.

Les Long’s Harlequin engine used two customer-supplied Harley Davidson pistons, cylinders, heads and rods. Long supplied crankcase, new crankshaft and camshaft for Depression-era $98

Designers looking for available electric motors and “plug-and-play”* complete systems may want to look at the 2015 Zero Motorcycle lineup. Since one Zero motor has flown at the Arlington, Washington Fly-in and at AirVenture 2013, we can attest to the demonstrated performance. Zero’s newer model motors, controllers, and batteries can be found on the latest bikes from the company.

Their specifications are certainly indicative of light weight and high performance. The least powerful unit in the Zero FX produces a maximum of 44 horsepower with 70 foot-pounds of torque, enough to accelerate this reasonably light bike from zero to 60 in only 4.0 seconds – within the range of an “average” Tesla S sedan. Since torque translates to the ability to twist a large propeller, this capability speaks airplane language.

Some of the lightness comes from the 20-pound “aircraft-grade aluminum” frame. Even the largest and most powerful motorcycle in their range has a 23-pound frame. The complete bike without rider weighs 289 pounds and can carry a 341-pound load, or 630 pounds total.

Your editor called Ryan Biffard of Zero to find out how much the components weigh. He generously shared the following:

He notes that Zero does not allow sales of components for aircraft, an understandable reaction in these litigious times. To save Zero and other companies any heartburn in this area, some have suggested buying a complete motorcycle, stripping the necessary parts and selling the remaining bits to recoup part of the cost. Another hint – contact a friendly dealer who can sell you replacement parts.

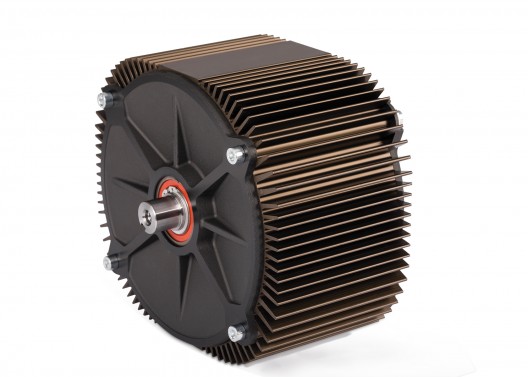

Zero 75-7 motor weighs only 38 pounds (compared to Long’s 80 pounds). It produces twice the horsepower

Ryan says “Each 2.5 kWh (nominal) battery module weighs 40lbs (give or take), so a 10kWh battery (one with 4 modules in it) weighs around 160lbs. Each module has its own built-in battery management system (BMS). This is roughly what Mark Beirele has in the cockpit behind the pilot seat in his e-Gull.

A triple “monolith” consists of three of the 2.5 kWh modules and weighs around 120 pounds. Mark is flying with the equivalent of a quad “monolith.”

Motors come in two sizes. The 75-7 weighs about 38 pounds (jibing with Mark’s numbers) and can climb at 40 kilowatts (54 hp.) for one minute, 30 kW (40 hp.) for several minutes, and cruise at 20 kW (27 hp.) indefinitely.

The 75-5 weighs about 30 pounds and can climb at 30 kW for one minute, 20 kW for several minutes, and cruise at 14 kW (18.8 hp.).

As Mark Bierele points out, though, the motors run at high speeds and thus need a reduction gear of some sort which adds cost and weight.

Ryan says the Sevcon Gen4 Size4 motor controller for the power numbers listed above weighs around seven pounds. If less power is desired the Size2 can be used: it would save a few pounds, and is a little bit cheaper.

Now for the bad news. Buying the complete bike is a bit pricey, but consider what you’re getting. Besides the motor and controller, the battery management system and all the appropriate wiring harnesses, you get a battery pack which is essentially a refillable “gas tank” with the cost equivalent of about one cent per mile. If Zero is correct on its lifetime expectations, that “tank” could last from from 158,000 miles for the largest battery pack on the smallest motorcycle to over 450,000 miles for the largest pack on the highest-performance model.

Zero’s web site lists the prices for their bikes from under $10,000 to a little over $20,000. Compared to 40-to-57-horsepower gasoline engines and the costs for induction and exhaust systems, the motors and controllers are comparable, and it could be argued that the batteries are far more economical than even today’s cheap gas fill-ups.

Other manufacturers offer comparable equipment with comparable specifications, but the Zero motors have actually flown and demonstrated their aerial capability. At this point, use of any electric motorcycle power system is still highly experimental and subject to some risk. That’s what experimenters have been facing for centuries, and gladly accepting the challenge.

*“Plug-and-play” should be taken only as a term describing pre-engineered systems that would be adaptable to a project. Plugs become too easily unplugged in severe conditions. One should follow proven practices in connecting electrical components – practices which usually involve more structurally sound fastenings.