A (Partially) Steam Engine in the Sky?

Pratt & Whitney announces that it, “Has been selected by the U.S. Department of Energy (DoE) to develop novel, high-efficiency hydrogen-fueled propulsion technology for commercial aviation, as part of DoE’s Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E).”

Their press release continues, “The Hydrogen Steam Injected, Inter‐Cooled Turbine Engine (HySIITE) project will use liquid hydrogen combustion and water vapor recovery to achieve zero in-flight CO2 emissions, while reducing nitrogen-oxide (NOx) emissions by up to 80 percent and reducing fuel consumption by up to 35 percent for next generation single-aisle aircraft.”

P&W claims their HySIITE engine’s steam injection will “dramatically reduce” nitrogen oxide emissions, a greenhouse gas. “The semi-closed system architecture is claimed to have thermal efficiency “greater than fuel cells,” and have lower operating costs compared to “drop-in” sustainable aviation fuels (SAF).

Steam Aircraft Engines Are Not New

The Besler Brothers of Oakland, California demonstrated a Travel Air 2000 biplane powered by their steam engine. The engine, derived from the Doble car engine to which they had purchased the rights, was nearly silent and had all the torque of a modern electric motor – obviating the need for a transmission or propeller speed reduction unit.

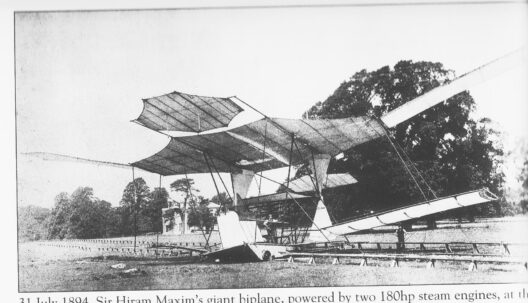

Even earlier, 1893, Hiram Maxim attempted flight with a huge steam powered craft.

In 1893, Hiram Maxim (the inventor of the machine gun) built a huge biplane-like test rig with twin propellers, each driven by a 180 horsepower steam engine. It ran along an 1800-foot (549 meters) straight track which allowed it to rise only a few inches into the air. In 1894, an axle broke during a test run, the rig escaped the restraining track, and it was in free flight for a few seconds before the crew shut down the engines. It might have sustained itself in flight — it certainly had ample power — but it had no controls other than two elevators, one forward and one aft.

Hydrogen Embrittlement

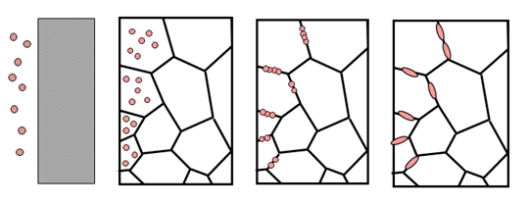

One issue that has prevented direct combustion of hydrogen in engines is the destructive nature of certain metals’ reactions to being in contact with hydrogen.

Industrial Metallugists, LLC explains, “Hydrogen embrittlement is a metal’s loss of ductility and reduction of load bearing capability due to the absorption of hydrogen atoms or molecules by the metal. The result of hydrogen embrittlement is that components crack and fracture at stresses less than the yield strength of the metal.”

Steam injection may help prevent the problem by mitigating intrusion of hydrogen atoms into the metal surfaces, but that is speculation without further information from Pratt & Whitney.

The chance to mitigate greenhouse gases, lower operating costs and use an increasingly available “green” fuel is a worthy avenue to explore.