Noisy airplanes are the bane of modern living. (Well, that and the myriad other intrusive sounds with which we are surrounded.) People can create and easily get signatures on petitions to close 70-year-old airports surrounded by 20-year-old housing developments, so General Aviation’s survival will at least partly depend on hushing our aircraft.

We’ve been privileged to see and hear the passage of e-Genius, Pipistrel’s G4, and Chip Yates’ Long-EAS with a Craig Catto propeller, which emitted a barely discernible howl when it pushed the airplane at full power to a new time-to-climb Guinness record at the California State Airshow in early October 2013, reaching 500 meters (1,640 feet) in one minute, four seconds.

This quest for quiet presses on the big airplane producers, too, anxious to be good neighbors and give passengers a less raucous flight. One engine make, Snecma, has been working on the problem since before 2009, when this report appeared in the blog Envirofuel.

“Volvo Aero will help develop open-rotor aircraft engines for the EU’s Clean Sky project in conjunction with Rolls-Royce and Snecma. Open-rotor engines are essentially large turbofan engines without the ducting around the outside of the fan. In open rotor engines, the diameter will increase to more than double existing turbofan diameters, allowing the engine to work with a larger airflow, regardless of aircraft speed. This means that the energy turning the fan will be utilized more efficiently, thereby reducing fuel consumption by 15 to 20 percent.

“Open-rotor is actually not a new concept. In the 1980′s open-rotor engines were developed when oil prices rose to USD40 per barrel. When the oil price later dropped dramatically, plans were shelved. Sound familiar? Volvo say aircraft with open-rotor engines can be in the air by the end of the decade but engineers will have to reduce the noise that is normally contained by the turbofan ducts on modern jet engines.”

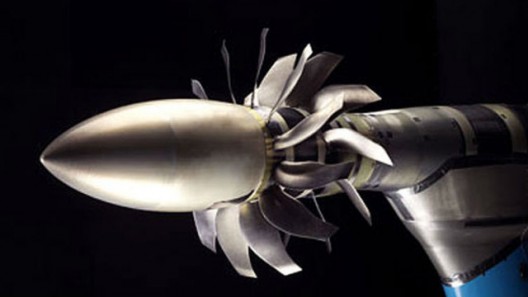

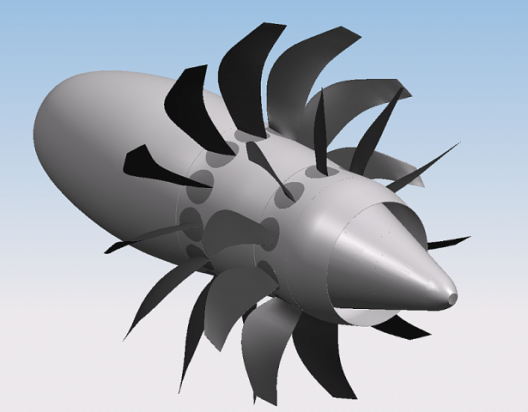

More recent attempts to realize the potential of an open-rotor engine have led to Snecma building a prototype that will be tested on an Airbus A340 in 2019.

Michael Gubisch, reporting for Flight Global, explains the core of Snecma’s M88 fighter plane engine will power two unducted, contra-rotating fans. Because the fans can be larger in diameter than those constrained by conventional turbo-fan engine, they can turn more slowly and push a larger volume of air. The demonstration unit should undergo ground tests in 2016.

Snecma, an equal partner with General Electric in developing an engine for narrow-body passenger jets in a joint venture called CFM International, has been conducting wind tunnel tests on a one-fifth scale version of the engine at the ONERA (“The French Aerospace Lab”) research facility in alpine Modane, France. Noise levels are lower, and are helping Snecma, GE and NASA resolve to push forward with full-scale versions.

Earlier attempts at producing an open-rotor engine produced much higher noise levels than conventional, ducted turbofans. Despite that, the open-rotor configuration was tested on a Boeing 727 and a McDonnell Douglas MD-80. The video comes from a different time, where the difference between 50 cents per gallon fuel and $1.00 per gallon could have profound economic consequences.

The partners wanted to lower noise, and Snecma research and technology director Pierre Guillaume says the new engine’s noise level “should be similar” that of the CFM International Leap powerplant, which will be in service on the 737 Max, the A320neo and the Comac C919 from China. The Leap will have a noise level 10dB below that of current-generation turbofans, according to Guillaume. If the open-turbo version can reduce fuel burns by 30 percent (even better than Volvo predicted), operating costs for jetliners could plummet.

“’After the tests at the end of 2013, we will be focusing on building a full-size prototype. That prototype should be ready for the [test] bench by the end of 2015,’ says Guillaume.”

Flight Global quotes Guillaume that, “The production stage will be particularly challenging due to the complexity of the engine’s rear assembly. While the core’s compressor section will be fairly conventional, the turbine will drive a rotating fan assembly, comprising a reduction gearbox and pitch-control system for the fan blades.”

The core of the Leap engine has been designed to work with potential future open-rotor powerplants, but will need additional standards to counteract potential fan blade failures. These obviously have very different forms, and who knows what algorithms had to be devised to account for the stresses on the swoopy blades?

Ground handling practices for these systems will revert to those of the “good old days,” with “Clear prop!” once again becoming a phrase heard around big airports. For that matter, aircraft designers might decide that the turbine can be supplanted by an even cleaner electric motor.

Comments 1

You are wrong about the noise. The propulsion systems that GE and Pratt & Whitney flew were very quiet; but the project got canceled because fuel prices started to drop and ‘people/passengers’ just thought ‘seeing props’ just was old, and not going to be accepted.

(Editor’s Note: Mr. Godston was a test pilot earlier in his career and project manager at Pratt & Whitney when these engines were tested at Edwards AFB.)