Every year, Labor Day weekend brings sailplane enthusiasts to Jeff Byard’s hangar on Mountain Valley Airport above Tehachapi, California. It’s a friendly get-together that always has challenges and surprises for the participants.

History on the Field

This year, attendees were treated to an opening talk by Jeff Byard titled “Soaring, Something for Everybody.” It lived up to its name, with a review of sailplanes of all types, with many examples right in the presentation hangar. For history buffs, jeff’s hangar, and Doug Fronius’ a few doors away, offer a glimpse of every type of hand-made soaring machine, including Doug’s recreation of Waldo Waterman’s 1911 hang glider, something which has been flown over the California coast.

Jeff’s collection includes a Slingsby SG-38 primary glider and T-21 side-by-side trainer (seen above in its native habitat, England). The T-21 fuselage rests on the floor to the right as one opens the hangar doors, and the wings in mid-restoration hang nearby. Jeff hopes to have this open-cockpit piece of history ready by next year to show how RAF pilots learned to fly gliders.

Four Concepts and a Favorite

Neal Pfeiffer followed with “Concept(s) for a Homebuilt Soaring Motorglider,” a look at how inspired home-builders might create a mid-performance touring motorglider – something one could take off and land on a small airport and use for trips from 200 up to 400 miles at speeds of 70 to 110 knots (80.5 to 126.6 mph) under power. This would be a nice cross-country tourer under power, and if conditions permitted, one could switch off the engine and soar at 24:1 to 31:1 glide ratios. Even though this is not contest-winning slipperiness, it would provide budget soaring expeditions for a couple without the cost of a towplane or the potential added costs and labor of an outlanding.

Neal Pfeiffer is restoring two ASK-14 motorgliders, powered by tiny Hirth four-cylinder, two-stroke engines

Neal showed four concepts, single and two-seat aircraft in sheet metal, composite, wood, and a final version in traditional steel-tube fuselage imaging a Wittman Tailwind with wood wings – somewhat like a modern form of a vintage sailplane or motorglider. All concepts but the last could be seen on Mountain Valley’s field.

What Happened to the Toilet Seat?

Andrew Angellotti had a provocative title for his talk – “Developing Flight Test Instrumentation Without the $30,000 Toilet Seat.” As with many home-grown approaches to “big science,” Andrew’s instrumentation for developing highly-sensitive instrumentation (some of which flew on Perlan 2) involved some big items. These included a load cell in a Styrofoam beer cooler, 3,062 pounds of water, a forklift, and a Dewar of liquid Nitrogen. His web site shows the refined and lightweight instrumentation that enables accurate performance measurements without breaking the flight test budget

Here’s a video of Perlan on the ground and in flight, with a “beauty shot” of his probe at the 2:49 mark.

Low, Slow, and Cheap

Yours truly reported on his slow but ongoing efforts to build the world’s cheapest electric aircraft, which will be an ultralight Kimbrel Banty, an all-wood craft from 1984. Mike Kimbrel sold his plans in 8-1/2” X 11” format for $25 a set, and by 1998 had sold 1,320 sets. 30 actual aircraft were flying by that time.

The big problem for your editor is keeping the aircraft inexpensive (“cheap”), forcing an investigation of brushed and brushless motors. Brushed motors can be controlled with a simple potentiometer, while brushless motors require a more complex and expensive speed controller. Batteries are still the most expensive part of the build and your editor is researching many possible ways to lower that cost.

Beauty, Speed and Strength

After lunch, participants enjoyed a double-header from Paulo Iscold with the construction of the Nixus sailplane – the first high-performance machine with total fly-by-wire control, and Eric Stewart showing how he followed strict discipline and ASTM protocols to perform, “Destructive Testing & Materials Characterization for an Experimental Race Plane.”

The pair has worked together on many projects and both managed to destroy big chunks of the sailplane and the race plane in their quest to build safe structures. For Nixus, the 92-foot wings were extremely flexible, part of the reason “fly-by-wire” was almost a necessity – much like that on Fred To’s 1982 Phoenix, an inflatable, 100-foot span, pedal-powered craft.

100-foot span Phoenix in 1982, during test flights in London’s docklands. Inflatable plane used model airplane servos on rudders, elevons and could be controlled by pilot with transmitter or by remote pilot on ground

Paulo’s Nixus was tested in a most spectacular way.

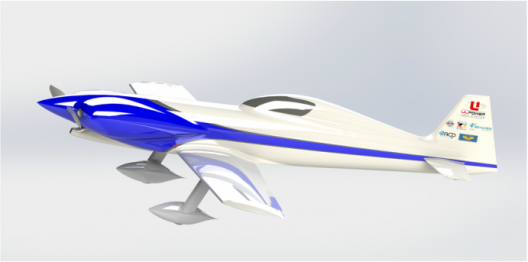

Eric’s SR-1 racer’s tests, so far, are on smaller scale, using “coupons” of specifically-sized samples of sandwich construction (layers of carbon fiber on either side of a foam core) to determine structural limits. He has built a light composites database from his research.

SR-1 will make record attempts in the FAI c-1a/0 class. Eric writes, “…Aircraft must weigh less than 661 lbs at takeoff, including pilot and fuel. With recent advancements in powerplants and lightweight components, our goal is to push the current record of 223mph to 275+mph. For regular updates, check us out at facebook.com/TheSR1Project.”

Where Will the Future Take Us?

Paul Gaines added another provocative title to the proceedings, “Understanding Another Stagnation Point- a Discussion About Aviation & the Next Generation.” He opened a lively discussion of how to bring young people into the sport, a matter of concern among the many grey-haired audience members. Although many ideas were floated, the subject remains an unanswered question.

(Stagnation point, in aeronautical terms, “Is a point in a flow field where the local velocity of the fluid is zero,” according to Wikipedia. A similar point occurs in human endeavors when all energy is lost in moving things forward. Aviation has reached that point several times in the past, and we are the stewards of the heritage that should be maintained. The future is our responsibility.)

That evening, following the potluck barbecue dinner, Dan Rihn and Doug Fronius staged a hilarious auction of things aeronautical and bizarre. The good humor and fund-raising bids ended the day on a high note.