Klaus Burhard publishes a wonderful news and blog site promoting ultralight sailplanes. His German site has been the source for many blog entries by yours truly, and the latest items from Klaus are of concern to anyone involved with electric aircraft.

He has reported in the last week on a disturbing incident with a UK-based HPH glass-wing 304eS/Shark FES “self-starter,” or self-launching sailplane. The airplane is a standard-class 15 meter (49.2 feet) wingspan plane. As seen in the video below, The FES (Front Electric Sustainer) motor on the nose swings a propeller which folds into the front contours of the sailplane when not powering the plane. When a pilot engages power, the rotation of the motor pushes the propeller blades out into the airstream.

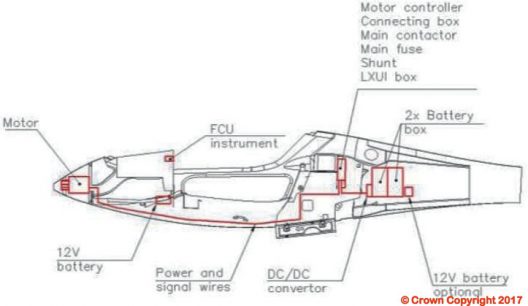

Two battery packs engineered by FES nest in a compact area behind the pilot. Each pack contains 28 high-power Kokam lithium-polymer batteries of 43 Amp-hours each wired in series to give 2.1 kilowatt-hours of energy. Packs operate at a range of 90 to 118 Volts. The father and son team of Matija and Luka Znidarsnic note that “Our latest GEN2 Battery packs have integrated BMS (Battery Management System[s]) and RADSOK high power quick connectors!” FES contains the batteries and BMS in proprietary composite boxes. Packs are designed for easy removal from the airplane for charging.

Arrangement of nose-mounted motor, battery packs behind pilot

A Really Hot Landing

Shortly after landing, an HPE glass-wing 304 eS/Shark FES sailplane “suffered a battery burn.” The August 10, 2017 incident took place at Parham Airfield in Sussex, the UK. According to Klaus Burkard’s blog. “During the roll-out, the 55-year-old pilot smelled fire, while at the same time smoke was pouring into the cockpit from behind. The pilot was able to leave the aircraft uninjured after a [rolling to a] standstill.”

Fire blew hatch cover off on rollout. Flames were extinguished by foam-type chemical

“According to the PIC (pilot in command), there were no specific incidents throughout the flight that pointed to battery problems. Only when putting on the [brake] he heard an unusual noise behind him. Upon exiting the cockpit, he found that the battery compartment cover was missing and flames and smoke struck the battery compartment. The detached battery compartment cover was later found near the touchdown point. However, this had no fire damage, only the rear carbon locking tab was broken. The cover was probably blown off as a result of a sudden increase in pressure inside the battery compartment.”

The pilot reported that in January, one of the battery boxes fell about 20 centimeters (eight inches) from his car to the ground. He apparently saw no damage to the case at that time. Because he did not mark or write down the ID for that battery pack, it was not possible after the fire to determine “whether the battery that had caught fire was the same one that had fallen out of the car before.”

An Earlier Incident

On May 27, 2017, at Benesov Airport in the Czech Republic, another 304 FES was dismantled and being rolled into a hangar following a recent landing. The front battery pack burst into flames and caused considerable damage to the sailplane. Both batteries were in the airplane and electrically connected to each other. According to Klaus, the flight and operations manual for the sailplane requires disconnecting and separating the connecting cables when moving the airplane. All switches were off, but the pilot reported going over a hard bump during the rollout.

Are these impacts enough to cause cell damage that can lead to a thermal runaway? Klaus thinks both incidents had nothing to do with the FES systems involved, but rather came from the batteries alone. Responding to European Aviation Safety Agency’s emergency airworthiness directive and its own investigation, FES has made changes to the battery packs and containers.

Klaus explains that the American FAA recorded eight battery fire incidents in 2013, nine in 2014, 16 in 2015, and 31 in 2016. “Thus, the number of incidents has more than quadrupled within five years.” (Klaus’s emphasis) Battery fires are rare enough, but consequential when they happen.

Not Wonderful Choices

Klaus explains that for ultralight sailplanes powered by any electric power system, a battery fire in the air is a major problem. One can’t jettison the batteries and popping the ballistic recovery parachute might cause it to ignite. The pilot’s only hope, in that case, would be to leave the airplane and parachute to safety.

Damage to frong battery box on British sailplane. Both incidents were”lucky” in occurring after a safe landing

Of course, alternative chemistries for batteries (such as LiFePo4 – lithium iron phosphate batteries), or batteries with solid-state electrolytes might provide a safer level of operation. Better monitoring of battery charge and internal temperatures at the cell level might give an early warning of trouble.

In the meantime, adherence to the airplane’s operations manual, care in handling the batteries, and diligent monitoring of motor and battery instruments could alert the pilot to points of concern.

Klaus Burkhard has a long and helpful list of links to publications which go into great depth on the subject, and provide worthwhile rules and suggestions from regulatory agencies. LZ Design, Luka’s firm, released a helpful analysis of and response to the situation. Batteries overall seem to have better safety records than gasoline or Jet-A, but all must be handled with care and reason.