Great Britain has recently allowed very light aircraft to fly under SSDR (Single-Seat DeRegulated) rules, which permit single-seat aircraft with an MTOM (maximum take-off mass) of not more than 300 kilograms (660 pounds) and a landing speed of not more than 35 knots (40.27 mph or 64.82 kilometers per hour). With weights and speeds a bit higher than those allowed for American ultralights, these would be desirable as a way to expand the number of aircraft flying under ultralight rules. How a machine such as the ProAirsport’s GloW will be regulated in America remains to be seen.

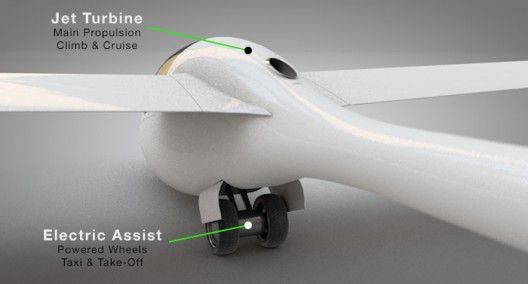

ProAirsport GloW includes jet turbine for climbing, dual electrically-driven wheels for acceleration

Formed in 2014, ProAirsport will built light aircraft around the new British rules while adopting ASTM F2564, Standard Specification for Design and Performance of a Light Sport Glider, as a way to meet light sport standards worldwide – including in America. You can see the abstract here, but the full set of standards costs $49.00 plus shipping.

The actual machine, shown here in computer renderings, will meet SSDR limits, and be powered by a Dutch AMT Titan microturbine that generates 40 kilograms (88 pounds) of thrust. The eight-pound jet sits in a fixed position, needing only to be flipped on and started to produce power.

Because jets have sometimes very slow acceleration when the throttle is advanced, GloW’s designers have added a pair of motorized main wheels to help overcome that lack. Electric motors have great torque for their size, even at zero speed. This combination of retractable“helper wheels” with a small jet to loft the sailplane to altitude seems to provide one solution to self-launching.

The little engine is thirsty, sucking down 36 ounces of fuel per minute. That means takeoff and climb to 2,500 feet will consume about 6.5 liters, or about 1.717 U. S. gallons of kerosene, diesel (including agricultural, recycled and bio-diesel types), jet fuel, or other approved form of go juice. A planned 34 liters on board (subject to change) would enable five take-offs and climbs to soarable heights. In flight, a cruising throttle would enable flight on 20-percent power, sipping one-half liter per minute, good for close to an hour of autonomous flight. (Editor’s Note: Original number for U. S. gallons of fuel was too low and was corrected by Howard Handelman. This little engine is definitely thirsty.)

The 300 kilogram MTOM has allowed GloW’s designers to use less expensive, heavier fiberglass construction, rather than the carbon fiber preferred to help keep U. S. ultralights within the 254-pound, FAR Part 103 limits.

Even though the jet can spool from minimum to full RPMs in four seconds and down from full throttle to idle in three seconds, acceleration of the 660-pound total weight is slow enough to require the use of a seven-horspower (peak output) wheel motor to kick start the takeoff.

According to ProAirsport, “Our high-torque brushless motor is a standard unit customized for our use profile and with a purpose built controller from the motor manufacturer for true technical compatibility… Electrically driven wheels also provide for taxi capability before take-off and after landing – without running the turbine.” The CAFE Foundation has promoted use of wheel motors to enhance acceleration in its proposed Sky Taxis.

Once airborne with the turbine shut down, time and distance become dependent on the pilot. The 13.5-meter (44.28-foot) wings are designed for a rate of sink of only 120 feet per minute and a glide ratio of 36.

Roger Hurley, the company’s head, uses the slogan, “Prepare to fly more, fly for less,” and promises a surprisingly low price for the new machine. With two prototypes under construction, one to meet British SSDR regulations and one that will suit U. S. Light Sport rules, we can hope that GloW will come with positive sticker shock and confirmation of its promised performance.

Comments 3

Ooh, that looks nifty! I’m concerned about the engine efficiency – 120 fpm sink rate at 36:1 glide ratio gives 49 MPH. At that speed, 88 pounds thrust is 11.7 HP. And 36 oz/min fuel rate is 22.5 gallons/hour, giving a sfc of 11.5 pounds of fuel per horsepower per hour. This shows why jet propulsion is seldom used at low speeds – and why piston engines with folding blades are usually used for this (typical 2 stroke sfc can approach 0.65 or less; 4 stroke can hit 0.45; gigantic diesels get down to 0.16).

All that said, this jet’s sfc of 1.53 pounds of fuel per hour per pound of thrust is actually very good for a small turbojet. I wonder how a pair would work in a small, fast design like the BD-5J? The price should be interesting, too, as turbine engines have historically been very expensive.

(Editor’s Note: Good critique of the microturbine and its thirstiness. As for the pricing, AMT’s pricing page shows numbers ranging from 8,599 euros to 8,944 euros. That’s $9,200 to $9,570. Depending on how much the glass airframe costs, prices could be in a desirable range for the complete airplane.)

At present this would have to be certificated in the US as Experimental – Exhibition and Racing. It’s too heavy to be a US Ultralight, and it couldn’t be Light Sport because you cannot use a turbine propulsion in a Light Sport aircraft (nor electric, either) – this was a frankly stupid inclusion in the rule (regulations should generally avoid taking a position on specific technologies).

There has been discussion about addressing the turbine efficiency issue by using the turbine to spin a generator, to turn a motor with a folding propeller: at low speed, the gains from using a propeller may outweigh the losses (and weight) of the conversion system. In this case, such a system would eliminate the need for the wheel motor.

Jim Horn asks about a small, fast jet design – there is one available, from Sonex (look up SubSonex).

Promo price now on the website http://www.proairsport.com. Regular retail price after this is still likely to be no more than USD 70,000 ex works. As with everything in life, if the production volumes can be good so too can the prices.

(Editor’s Note: We wish Roger and his team success, as this has to be the least expensive jet airplane in the world.)