A Seven-Year Stealth Project

Opener doesn’t sound like the name of an airplane company, and BlackFly doesn’t sound like a very charming name for an airplane. Maybe that’s how the developers of an eight-motor personal flying machine got away with it for so long.

Beth Stanton, who writes wonderful articles about futuristic projects for the Experimental Aircraft Association’s Sport Aviation magazine, alerted your editor about a project that sneaked under the radar for the past seven years.

The airplane looks a bit like a single-seat Vahana, Airbus’s two-seat air taxi currently under test in eastern Oregon. Where Vahana is just beginning flight tests, BlackFly has over 12,000 aerial miles carrying a payload in 1,400 flights. BlackFly has gone through 40,000 cycles on its power system, equivalent to 25 circumnavigations of the earth, according to the company.

Four generations of BlackFly, showing its evolution over the last seven years

Three fail-safe flight control systems manage redundant motors, elevens, and batteries. Batteries are arranged in a distributed, isolated system.

Pilots are constrained and protected from doing anything too silly. Software provides control limits within the design’s flight envelope and the potential to remain within (or outside) designated geofences. If one gets into trouble, a return-to-home button, soft landing assistance, a “low-power glide mode,” and ballistic parachute recovery can save the day.

Its outrunner-type motors were apparently developed by Marcus Leng, Opener’s founder and CEO. How are they significantly different or better than commercial off-the-shelf items found at hobby shops?

A Worthwhile TV Report

Two reporters do a knowledgeable and professional job of presenting the machine and the case for it. John Blackstone, a long-time technology reporter for CBS and anchor Reena Ninan give the background and some responsible assessments of what the team at Opener has accomplished. They even visit the Hiller Aviation Museum in San Carlos, California – one of your editor’s favorite places. It’s nice to see a non-judgemental, sober review of this emerging technology.

Note Blackstone’s startle reaction when the motor fires up, and the reading which shows 108 pounds of thrust (your editor’s guess as to what is being measured).

A Board of Adventurers

Marcus Leng, the founder and CEO of Openers, earned a recreational pilot’s license when he was 18. He graduated from the University of Toronto in 1983 with a mechanical engineering degree and worked until 1986 in multinational corporations. Forbes quotes him as having big plans. “Opener is re-energizing the art of flight with a safe and affordable flying vehicle that can free its operators from the everyday restrictions of ground transportation.”

Alan Eustace did more than intellectualize as a Senior Vice President at Google – he actualized the world’s highest parachute jump. A great deal like BlackFly, his jump equipment was minimalist, just him in a special space suit with all necessary life support equipment and a release mechanism to separate him from the large balloon that carried him aloft.

Ed Lu, advisor to the project, “flew on two Space Shuttle flights, one Soyuz flight, and served a 6 month mission aboard the International Space Station. Since retiring from NASA, Ed has worked at Google as Program Manager for Advanced Projects, and at Liquid Robotics.” His flight experience, coupled with a degree in electrical engineering from Cornell University and doctoral degree in applied physics from Stanford University give him a unique ability to help on different aspects of BlackFly.

Ken Sasine, also an advisor and President of Precision Wings LLC, a flight test consulting firm, brings a wealth of experience. With time in over 100 different aircraft and 16,000 hours flight time, Ken can evaluate the complete flight spectrum of this unique design. He is a graduate of the USAF Test Pilot School and former instructor at USAF and National Test Pilot Schools.

Is There a Future for Such Personal Aerial Vehicles?

As a possible feature bonus, BlackFly can be trailered on a solar power/hangar platform for off-grid electric flying.

As exciting as the videos are, and as well-developed as this product is, it still costs some variable SUV price. Potential customers will balk at different price points from a $35,000 SUV to a $150,000 SUV. It’s small enough that perhaps 3D printing could crank out wings and fuselage tubs at a reasonable cost in sufficient quantities to create a mass market. Certainly, the motors are comparable to model aircraft units in the $300 to $1,000 range. Even with the costs of controllers being roughly equal to motors, eight motors won’t cost over $16,000. Batteries are still a big part of the costs here.

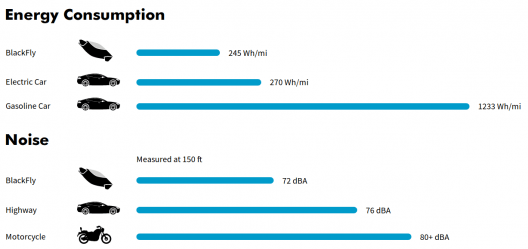

BlackFly’s low energy consumption and low noise may help offset the high initial cost and make it a plausible PAV

Depending on how it’s made, the airframe seems simple and light enough to be made inexpensively. The magic, of course, is in the control system, which has to be a custom hardware/software offering. But one sees hobbyists creating home-made machines that provide stability and multi-motor control from commodity-level electronics. Will redundant cheap components allow a level of reliability that will ensure safe passage?

Aircraft, because of small production runs, are expensive and must function perfectly all the time. That helps make them more expensive, pound-per-pound, than toasters or dishwashers. Still, one wonders if efficient manufacturing techniques can bring the costs down.

BlackFly, one of many multi-motor, multi-rotor personal aerial vehicles rising over the horizon, is a precursor of even more such products sure to appear soon. They have a gutsy Board and a great sales pitch. Their success will lead to increased interest in the long-hoped-for PAV.